Author : Jos Hermans

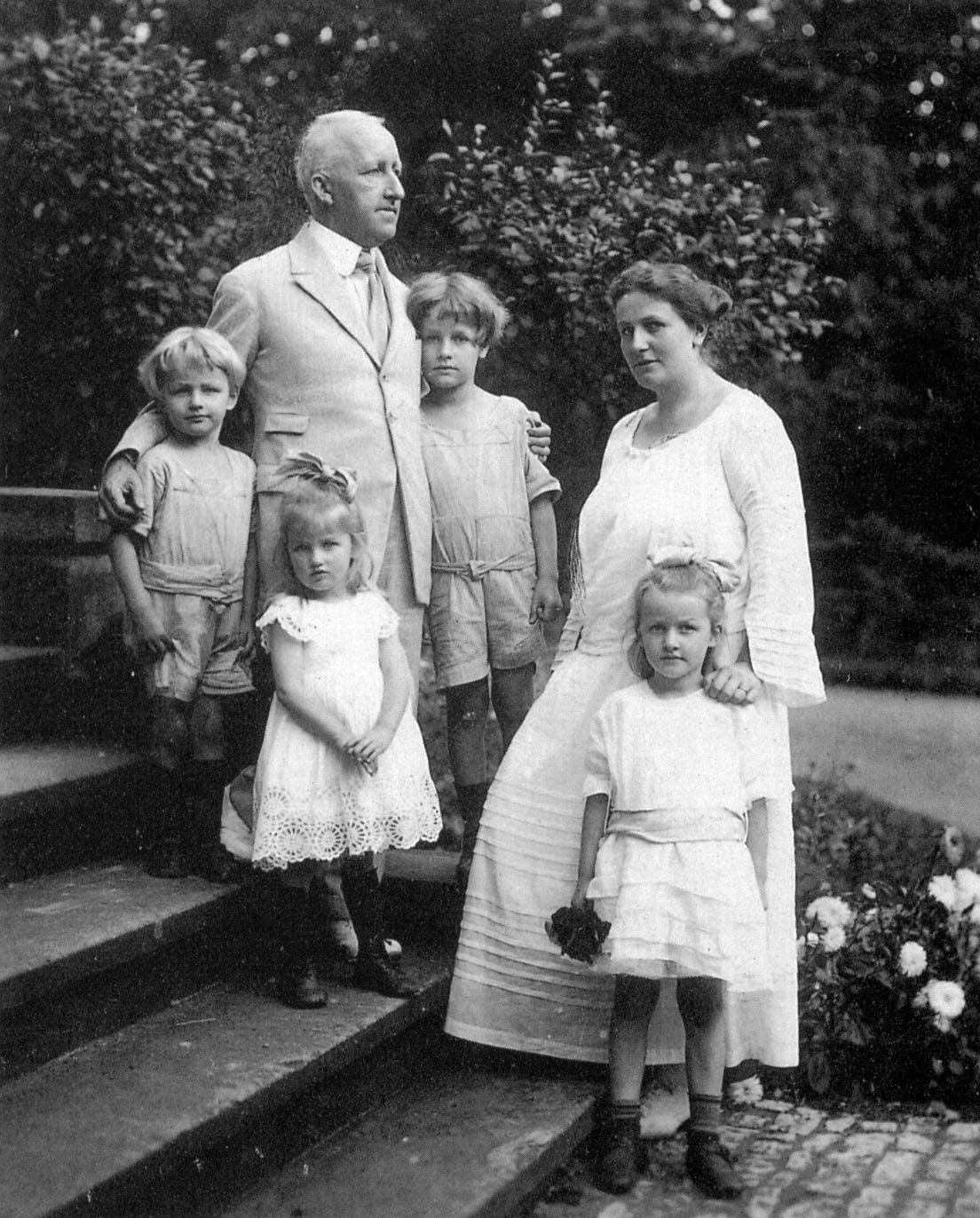

"My parents called me Siegfried. Well, I didn't smash any anvils, slay any dragons or conquer any flames. Nevertheless, I hope I have not been entirely unworthy of the name because fear is certainly not part of my nature." (SIEGFRIED WAGNER, Erin…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Leidmotief | Leitmotif to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.