Bayreuth is the only opera that's any good to me

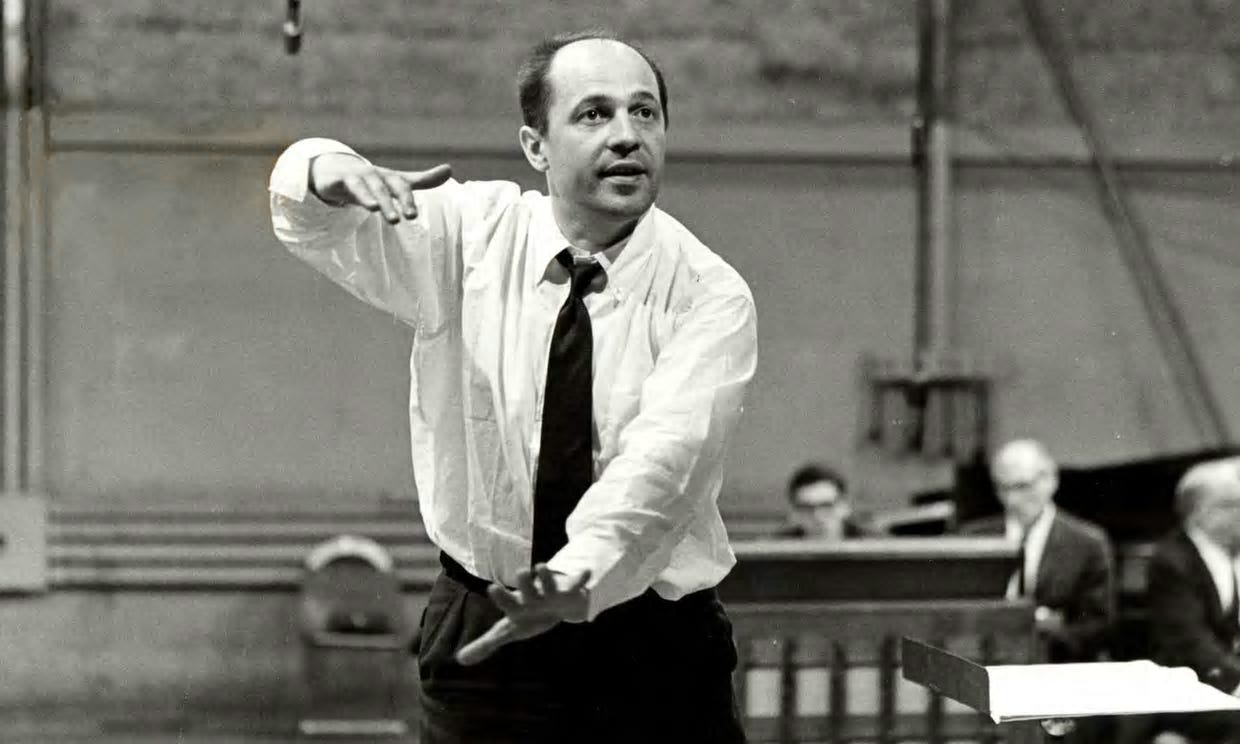

Living with thirty kinds of salami : a portrait of 75-year-old Pierre Boulez anno 2000.

Auteur : Jos Hermans

“The simple fact that Bayreuth, after the brilliant inauguration of the Festival, attended by all the ruling aristocracy in 1876, was condemned to silence from 1877 to 1882, with the première of Parsifal, left Wagner bitter and, even more so, perplexed. Was his dream of a national art premature, or was it a mere illusio…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Leidmotief | Leitmotif to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.